![]()

| Starboy |  |

Copyright 1956 by Carl L. Biemiller

Illustrated by Kathleen Voute

![]()

| Chapter One | Chapter Two | Chapter Four | Chapter Five | Chapter Six |

| Chapter Seven | Chapter Eight | Chapter Nine | Chapter Ten | Chapter Eleven |

| Starboy's Home | C.L. Biemiller's Home |

Chapter Three

The wonder of having a starboy for a visitor was very real to Johnny. It was an even stranger situation for his father. Visitors from space! It could have been awkward for the Man from Out There and his son, Remo, too, but they seemed quite comfortable as they sat in the big living room of the Jenks' farmhouse. So did Mrs. Jenks. She seemed perfectly happy.

"You must know that we're bursting with questions," said his father to Arcon.

So was Johnny, and the first big one popped into his mind. He did a thing he ordinarily would not do. He interrupted his dad.

"How did you put that fire out? You did do it, didn't you?"

Arcon chuckled. "Get me a glass and I'll show you," he said.

Johnny streaked from his chair skidded into the hallway and through the door into the kitchen. He was back in less than a minute with a glass. He handed it to Arcon who took it gravely.

There was a thimble on a table near his chair and he placed the glass over it. "Now," he said, "just suppose that thimble were the barn and it's burning. It has to have air around it to burn, Johnny. It can't burn without the oxygen in the air. If there were something like this glass pressed down over the barn, something which shutout all the air, something which put a big nothing…"

"A vacuum," muttered Mr. Jenks.

"Exactly," said Arcon. "A big nothing over that barn," he continued, "the fire would go out. Well, Remo and I created a vacuum over the fire. It worked just like the glass would. The fire was snuffed out."

"Our physicists would like to know how you drop a vacuum from a moving ship," said Mr. Jenks. "I might as well tell you now, Arcon, I work for the government. I called our Washington people as soon as my wife told me your ship had returned. They'll be curious. They'll send guards for Johnny again. They'll want to know every secret about your saucer, about you and where you come from, about Remo."

"I know," said Arcon gently, "we've studied your world a long time. I remember the harm I caused last year by giving Johnny the little metal toy, the marsquartz space-a-tron. I had forgotten that, because it represented something new on earth and was of apparent value, it would cause trouble. I had forgotten that there were men who would harm a child because of a simple metal and their own greed. The fault was mine, but I was fond of your son. I still am."

"Nevertheless," said Johnny's father, "there will be men here, eager and anxious to pry into your secrets. I feel that you should know."

"Johnny,' interrupted Mrs. Jenks, "take Remo out to the kitchen and help yourselves to milk and cookies."

"What's milk?" asked Remo.

Johnny laughed. If Remo were really going to stay and visit, what a time they were going to have. "It's a white drink and it's good for you," he said. "Let's go." They left in haste, each of them still a bit shy with the other, but each of them anxious to please.

"Remo does not know what milk is," said Arcon softly, "but he takes Johnny's word that it is good for him because he can see a little into Johnny's mind and he believes.

"It would be nice if men could see into each other's minds and believe the good which is there." He paused carefully. "You know that we are not earthmen. There are worlds like your own in space, and men upon them. Because our world is older than yours, we have had time to learn more than men here.

"But as men live, they learn that all life forms everywhere are precious and should be helped by all other life forms. Further, we are an exploring people. As our civilization grew greater, the more we sought to help others and to know more about all the galaxies we could reach. That's why saucers visit earth.

"I know something of your problems, Mr. Jenks. We have taken certain precautions. What does concern me is this, and it is a great favor I ask for your world and mine."

Mr. Jenks leaned forward in his chair, a serious, intense frown upon his face.

"It is important that our children know yours. You have atomic power now. Within a near future the youth of this planet will also reach for the stars and the outer worlds. It is not too early for the children to meet and learn about each other. May Remo visit with Johnny here at your home, live part of his life as Johnny does for a short time?"

"Yes," said Mrs. Jenks before her husband could say a word. "is there anything special I should know about Remo?"

"Nothing that you won't learn, " laughed Arcon. "Some of it may surprise you—his strength, for instance. He comes from a world where the force of gravity is greater than your own. His muscular ability has grown to meet that condition. He gets dirty, hates baths, and he is dying to see a baseball game..."

"And you're forgetting to tell us that he recites the Einstein theory," grunted George Jenks.

"Not quite," Arcon laughed. "He has been carefully conditioned for this visit because I knew Johnny so well at one time. Remo is one of our honor students, a boy among others whom we have selected to visit earth from time to time. He has been particularly schooled for his opportunity."

There was a crash from the kitchen. It pulled Mr. And Mrs. Jenks and Arcon to their feet. They moved to the doorway and listened. They heard Johnny's voice yelling

"Great, Remo, do it again, do it again!"

There was another crash.

"You fell over the same chair," cried Johnny.

"Noisy game," muttered Mr. Jenks.

The parents moved to the kitchen and peered at the boys.

Johnny was sitting on the edge of the sink. He was watching the ceiling. Remo was crouched alertly in the middle of the floor, his gaze on the ceiling too.

A big, bumbling fly flew from a lazy half-circle and landed.

"Go," yelled Johnny.

Remo flexed his knees, sprang from the floor, and popped his hand over the fly.

"Got him," reported Johnny.

Remo landed with a thud on the floor. He laughed.

Mr. Jenks looked at Arcon. ""Those ceilings are twelve feet high," he said.

"We can jump pretty far in this light earth gravity," grinned Arcon.

"You boys go out to play," said Mrs. Jenks firmly.

"A moment," said Arcon quietly. He walked across the kitchen floor and put his hand on his son's shoulder. For several long seconds he gazed deeply and fondly into the boy's eyes. "Go now, Remo," he said.

Johnny and Remo darted for the back porch.

Arcon shook hands with Mr. Jenks. "Walk down to the ship with me," he asked. " I want to show you something for your great hospitality." He turned to Mrs. Jenks. "Mary Jenks," he said very softly. "There is a woman much like you in my home. She would be happy to be your friend, and were circumstances different, to know your Johnny. Thank you for both of us, and good-bye."

The meadow was still the meadow, empty and green and quiet unless one chose to hear the busy life going on among the grasses. Arcon gazed at the sky, and as he did so, the saucer shape appeared before them, still spinning, still shining with a light that was not one with the day, yet blended with it.

"Look, George Jenks," said Arcon. He waved a long arm to the vault of the blue. There high in the curve of the heavens, almost pinpoints of swirling color, were two more flying saucers.

Arcon grinned.

"Pretty, aren't they?" he said. "And as long as Remo is here they will be nearer than you think—a simple precaution."

"I'll do the best I can," said George Jenks. "So long." He watched Arcon climb into the ship. He watched a long time, until there was nothing to see but a Cooper's hawk chasing a young robin into the fringe of woodland while a crow sentinel squawked a general alarm. He never saw Johnny and Remo leave the back of the house and take the long length of dirt road that led to the lower reaches of the Applegate farm.

"You wanted to know about milk," said Johnny as they scuffed their way down the dusty road. "I'll show you were it comes from. Mr. Applegate has a lot of cows. They'll be down by the creek in his lower pasture about now. They lie in the water to keep the flies off them. You know about flies. You caught one."

"Then Johnny laughed suddenly. "You might not like milk when you see a cow," he said.

Remo grinned. "You are thinking that cows are pretty funny-looking beasts," he said, "and that I might think them dirty because they are full of mud as well as being funny-looking."

Together they thought about cows.

Cows are stupid, gangling animals. They drip when they chew. They eat the same dinners three times. Cows bump into each other and fences. Cows can stand all night in the rain and not know that it's raining. Cows break down fences and eat green corn, which makes them sick, and it's hard to tell when they are sick because their faces always look sad.

Johnny and Remo laughed and laughed about cows. And because they laughed so hard together much of their strangeness and all of their shyness melted and became friendship.

"Wait till we see goats," said Johnny.

There was something about cows that Johnny might have remembered but he didn't. He never thought about it at all as they reached Applegate's meadow and slipped between the strands of barbed-wire fence. That was that cows have husbands called bulls.

Old Mr. Applegate could have reminded him. He was sitting on the back steps of his house wondering why corncob pipes always went out so much. He happened to look from his hilltop house site across the cornfields, now hip-high in green stalks, across his alfalfa fields, now in stubble from the second hay cutting, to his lower meadow where the narrow creek sparkled in the sun before vanishing in the grove of willows and locusts. He could see his herd. He could see the corner of his fence and the road, which mounted to a sandy knoll, which was real hill-high at that point.

He saw Johnny and Remo crawl through his wire fence. The old man had eyes as sharp as a kite's. He chuckled. Kids, kids, they wandered aimlessly and as busily as dogs in the full moon. Seems they needed more these days than he'd ever had. That talk about the science laboratory for the new school addition. Where was the value for the money? Maybe he didn't know much about boys today but suddenly Mr. Applegate sat bolt upright.

His Holstein bull was in that pasture. He had told one of his hired men to put him there that very morning. That bull was bad-tempered, hard to handle. It didn't have much respect for men. It just might take a notion that it didn't like boys.

Old Mr. Applegate heaved to his feet. He'd ride down to the pasture in the Model-T before something happened. He could park the Ford on that hillcrest in the road and take a look around. If he couldn't see the boys he could walk back into the creek grove for them. Boys, he thought, boys. Well, if children could think like adults the world might not need adults and then where would be the sense of having old men?

Johnny and Remo weren't thinking about anything in particular as they walked across the hummock-lumpy meadow to the stream.

"Let's take off our shoes and wade a little," suggested Johnny to Remo. "We can walk right up the creek and see the cows."

Johnny slipped off his sneakers and tucked his socks into the toes. Remo pulled off his boots. Together they jumped off the little bank to the gravelly creek bed.

"Johnny, this is great," said Remo, a note of wonder in his voice.

"Aren't there any creeks where you live?" asked Johnny.

"Water is precious on my world," answered Remo gravely. "There is nothing like this."

Remo was right, thought Johnny. There is nothing like wading a fresh-flowing runlet in the summertime. The water is cool. The half-muddy, mostly sandy bottom squashes between your toes and the little, fleeing, darting fish scoot away from your feet to hide beneath the overhanging banks. All the prickles that get on bare legs from walking in tall grass disappear in wet spray.

They walked up the stream into the grove where most of the cows were lying down trying to make their tails switch to the backs of their necks where the flies buzzed the thickest. Others were standing in the water blowing bubbles in the creek with their noses.

Remo and Johnny walked out of the creek and sat down on the bank. They were dwarfed among cows which blandly pretended not to see them.

Meanwhile Mr. Applegate was chugging down the winding road trying to watch the pasture and the ruts at the same time while the Model-T lurched ahead. He came to the fence corner, turned the ignition key, and stopped the car. He looked along the creek but he couldn't see the boys. He couldn't see the bull either, and that bothered him. Oh, beanpoles! Well, he'd hike in and look around. Because Mr. Applegate got twinges from wet feet, he did not wade into the creek as Johnny and Remo had done. Consequently he had to go the long way around one side of the pasture to get into the grove. Johnny and Remo heard him coming before they could see him.

"Let's go home," said Johnny. "Somebody's coming and I don't think Mr. Applegate or his hired men would like us in with the cows. They might think we were making them cranky, and cranky cows don't give much milk. This hot weather bothers them enough."

Johnny was right. Hot weather does annoy cows. But bad bulls which are always annoyed anyhow are meaner than ever when the summer sun rims their eyes with sweat and the goading flies sting deep and the strangeness of man-smell within the herd reminds them of pushing and beating and old pains.

The Holstein bull, his head lowered and his red eyes suspicious, watched the boys as they rose to leave the pasture.

Johnny saw him first. He stopped. "Remo," he whispered, "be careful. Don't move quickly." He pointed to the bull some thirty yards away across a patch of open meadow from where they stood on the creek edge. "That's the bull. He looks mean."

Remo could sense the electric thrill of alarm in Johnny's mind. He gazed calmly at the bull and remained still, willing to learn from Johnny about this strange world. As he waited he could sense also the rising tide of hate he caught fleetingly from the beast brain of the animal.

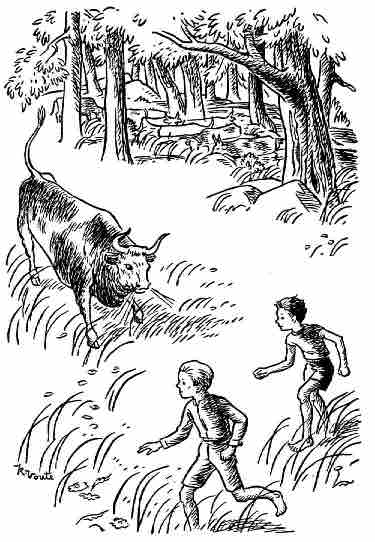

The bull moved closer, his head shaking slowly from side to side, the sunlight glinting off the yellow-tinted horns. It stopped, unsure and pawed the ground. It move still closer, now blowing foam from its nostrils, then, without warning, it humped its mighty back once and charged directly for the boys, its hoofs scarring the soft meadow ground. It was a creature of hate and ready to kill!

The bull moved closer, his head shaking slowly from side to side, the sunlight glinting off the yellow-tinted horns. It stopped, unsure and pawed the ground. It move still closer, now blowing foam from its nostrils, then, without warning, it humped its mighty back once and charged directly for the boys, its hoofs scarring the soft meadow ground. It was a creature of hate and ready to kill!

"Run for it, Remo!" yelled Johnny. "he's after us! Oh, run hard, Remo!"

Remo sprang lightly to the left, angling away from the charging bull, out of harm's way, but as Johnny, stretching his legs into a sprint, moved away from the bank, his feet slipped in the grass. He fell. He fell directly in the path of the onrushing beast.

From the corner of his eye and out of the curiosity, which stirred within him about this queer creature, which made him want to watch, Remo saw Johnny go down. Without hesitation he turned and streaked back. Legs flashing in an incredible burst of speed, he crossed the bull's path before the startled eyes of the beast, and literally under its very nose. As he did so he reached out and flicked one quick-grabbing hand at a lowered horn. He yanked and kept running.

The bull stopped dead in mid-charge, almost as if it had crashed into a stonewall. It flipped over upon its side and fell with a crash that made the meadow tremble. It lay there stunned and weakly moved its legs as if trying to rise again.

The boys panicked and fled for the corner of the pasture and the road, gathering speed with every stride, with Remo moving steadily ahead of Johnny. They ducked into an adjacent field, which led to the Jenks' farm and paused for breath.

"Remo," panted Johnny. "What did you do?? What did you do?"

"I don't know," said Remo. "Not exactly. I think it had something to do with timing. I just yanked as hard as I could and the bull fell down. It didn't seem hard at the time, and to tell you the truth, I don't think it was but I just don't know. Do you think the man we heard will be angry?"

Mr. Applegate was not angry. He had seen the entire incident from his side of the grove with a clear view through the trees. He was upset. He was baffled. He was astonished, but he was not angry. He shook his head. He muttered to himself. "Applegate, Obed Applegate, you're an old man on a hot day and maybe a mite sun-touched. You didn't see that happen. Not you. No small boy ever reached out and threw a twelve-hundred-pound bull for a loop. No, sir, that bull slipped and fell down just in time. It fell plumb over its own dumb feet and its own anger."

He watched the bull get to its feet and stand shaking its massive head. Then he walked back along the creek bank and picked up Remo's boots and Johnny's sneakers before he hiked to the road and got into his Ford. It's fun growing old, he thought. It's like being a boy again. You can believe in things and not care what people think. I knew there was something queer going on around here today. First, that barn fire and then a boy throwing a bull. My, my, how those boys ran…

When he got back to the house he called the Jenks' farm. He got Mrs. Jenks on the telephone.

"Mrs. Jenks," he said, "this is Mr. Applegate. I've decided not to send your mister a bill for my hay, and you tell your Johnny that he and his friend left some shoes in my pasture. They can stop at the house and pick them up. By the way, Mrs. Jenks, have you got a little boy over there strong enough to grab a bull by the horns and throw it on the ground?"

"Well," answered Mrs. Jenks ever so slowly and carefully, "Johnny has a friend visiting with us for a few weeks…" She paused.

"I'd sure like to meet him," said Mr. Applegate.

| Chapter One | Chapter Two | Chapter Four | Chapter Five | Chapter Six |

| Chapter Seven | Chapter Eight | Chapter Nine | Chapter Ten | Chapter Eleven |

| Starboy's Home | C.L. Biemiller's Home |