Johnny's father was a physicist, and physicists are special people. They are the men who work with the atom bomb, for instance. They are the men who study energy and energy is heat and light and motion. But even though Johnny's father and all his laboratory men had examined the little ball, nobody knew what it was.

"Molly," Dad said to Johnny's mother, "we've sent our reports to Washington and we're supposed to be the best men in the field. We can't tell them anything."

"Suppose," asked Johnny's mother, "that Washington want s Johnny's gift down there. If it's as important as you say, why would they let him keep it?"

"Because it's mine," said Johnny. He had been listening to his parents' talk.

Johnny's father looked very seriously at Mother and said softly, "That's one reason, dear. I've managed to convince them that there might be others."

Mother put her hand to her throat for a moment. She looked worried. "You mean that Johnny's Man from Out There might be interested in what he does with the little ball?"

"Go out and play, Johnny," said Daddy.

Johnny went, and took his sort-of-a-marble with him.

In the woods at the end of the pasture there was a fallen oak. A chipmunk lived in a hole near its tapered edge. A squirrel had once nested in the same place, and a family of field mice had a whole apartment house underneath a section of the trunk which had broken off when the great tree fell. Weeds grew thick along the trunk, and when Johnny walked on it, it was like walking along a bridge over a waving green sea. Where the giant roots had pulled away from the rich, brown earth, there was a wonderful natural cave. Some of the old roots hung over it just like a roof. The cave was one of Johnny's favorite places to play. It was where he went now.

He thought about going over to Mr. Jervis's place to see if Nicky, the son of Mr. Jervis's hired man, wanted to do something. He thought about taking Minstrel, his Airedale, along, but it was hot, and Minstrel always went down to Jervis's creek to soak with the cows in hot weather. He thought about watching television. But they did not put the baseball games on in the afternoon any more, just programs about women cooking or talking about their hair. Before Johnny knew it, he was in the cave.

He took the sort-of-a-marble out of his pocket and rubbed it against the scab on his skinned knee. The little ball felt cool and smooth and somehow easing. He held it up to his eye and squinted, but he could not see through it. It was milky with a silverish tint.

"You really are something," he said to the ball, "and you made Daddy believe that I saw a saucer even if he didn't want to believe that I saw it. I'll bet you're a trick ball just for me, no matter what they say."

There was nobody around and the woods were still, except for the usual daytime buzzings. No matter how quiet a woods seems to be, there is always a lot of noise if a person cares to listen. Johnny stood up and closed his eyes. He held the little ball on his outstretched palm and imagined himself in the center ring at the circus, with the crowd all still and only a lion snorting in the animal tent nearby.

"I will now give you Johnny the Great and his magic ball," he said in a solemn voice. "Ball, you will now turn red and stay in mid-air all by yourself."

He could feel the coolness of the ball in his hand, and then he could not feel it at all. For a long second he kept his eyes closed. He closed his hand but still he could not feel the ball. Then he opened his eyes.

The little ball was sitting right in mid-air. There was nothing to hold it up. Nothing under it. Nothing over it. But there it was. It was red and glowing.

Johnny sat down suddenly. The ball fell at his feet like a big raindrop, and he stared at it for another long second-hard. Do that again, ball. Do it again. He thought the command without saying a word. The little pellet rose and glowed. It hung like a jewel before him.

Johnny could feel a bubble of excitement within him, but he was not a bit afraid. "Now, ball," he said softly, "make a circle. Go round and round where I can see you. Not too far. Just round and round."

The red dot moved. It made as nice a little circle as you would ever want to see.

Come back, ball, thought Johnny, and held out his hand. The ball nestled into it gently and the red glow vanished.

Then, just as it had on the evening when he saw the saucer and me the Man from Out There, a voice spoke in his head. It was a friendly voice, and one that he knew. It was the Man, and he was chuckling. "Congratulations, Johnny. You made it work. I knew you would."

"Where are you?" asked Johnny loudly

"I guess you'd say about two hundred miles over the North Pole," said the voice. "But that's distance, and miles don't matter to us. You can hear me, can't you?"

"Sure," said Johnny, "but how?"

"Well, you know what a telephone is, don't you? You know what a radio is. You've seen television and listened to it, haven't you? Those things are only machines for carrying voices or sounds or pictures. The gift I gave you is sort of a machine to carry thoughts. It makes it possible for me to think to you, just as the telephone would let me talk to you."

"How did I make the ball move around?" asked Johnny breathlessly.

The Man from Out There laughed. At least Johnny suddenly knew he was laughing. "You thought what you wanted it to do. You thought hard enough to make it move. Listen to me carefully, Johnny, and I'll tell you an old secret. Suppose you wanted to drink some milk. The milk is in a glass. Well, first you think you want to drink it. Then your think tells your arm and hand to reach out and pick up the glass. Next your think tells you to open your mouth. So you move your arm, your hand, and your mouth, and drink your milk. Easy, isn't it? You arm and hand and mouth are working for your mind. Well, Johnny, if your mind was good enough and you practiced with it enough, then your mind wouldn't need any arms or hands. You could actually think that glass to your mouth."

"Holly smokes!" breathed Johnny.

"You'll do, youngster," said the voice in his head. "Now, Johnny, tell your father that the little ball is a substance called marsquartz. Tell him it's a new element. That is, if you feel that you can tell him anything without upsetting him. He'll know what you mean. All right. Now ask me the question that you want to ask."

"I guess you know it already," said Johnny. "If I think hard enough to make the little ball do anything I want it to, will you talk to me sometimes?"

"Yes."

"About what it's like Out There?"

"Hmmmm," breathed the voice in Johnny's head. "Maybe, Johnny. Good-bye."

Johnny put the little ball in his pocket and crawled out over the hump of banked earth which formed the lip of the cave under the oak roots. He had to tell somebody. A secret as big as the one he held was bigger than big. It was immense, much too big to keep to himself. Dad was interested in the little ball. Dad was serious about it. If Dad thought there was something wonderful about the sort-of-a-marble, then it would be all right to tell him what it could do.

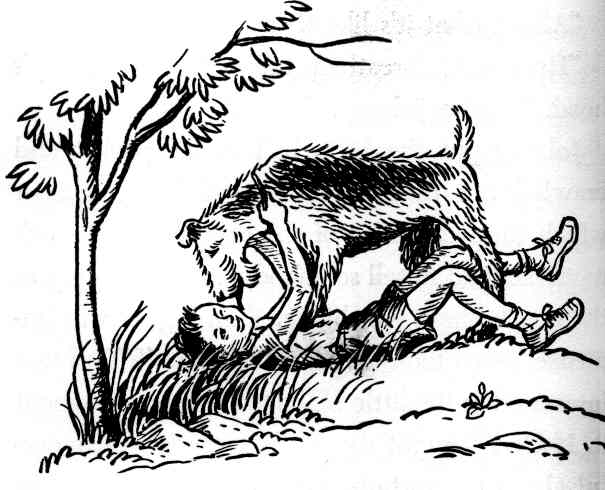

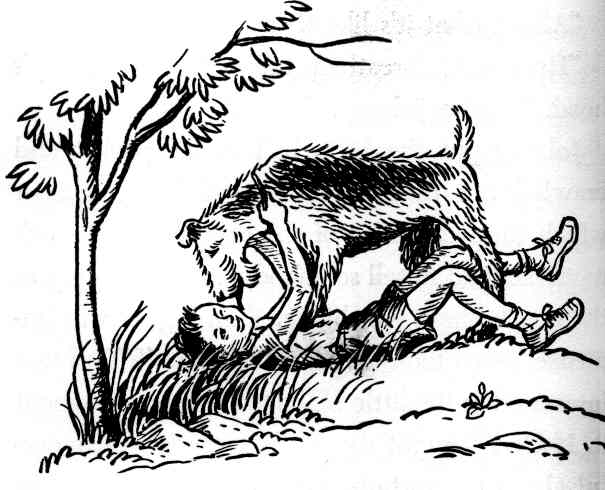

Across the pasture he could see the road from Mr. Jervis's place. Minstrel was trotting through the sand, and he could see puffs of dust from Minstrel's feet. Johnny yelled. Minstrel turned his shaggy head into the wind, charged off the road, and dashed down across the meadow toward him. Johnny ran to meet the dog and they bumped into each other and fell into a knot on the grass.

Minstrel put one big paw on Johnny's chest and licked his face with a tongue that felt like a stiff bath towel.

"Minstrel," said Johnny lovingly, "you're a mess, a sloppy mess." Together they ran toward the house.

Dad was waiting for them. He was standing on the back porch with his eyes shaded by an upflung hand. When they jumped the three wooden steps from the back driveway to the porch, he grinned at them. "Come on in, you two. Johnny, I want to tell you something, but I want Mother to hear it too."

"Is it a surprise?" asked Johnny.

"It's a surprise," said Dad. "Maybe you'll be taking a trip with me-to Washington. There are some men there who want to meet you and your marble."

Washington, thought Johnny! A real trip with Daddy! What fun! But then his face fell. Would they try to take the little ball away from him? Would he have to tell them about it? He would tell Daddy, of course. After all, the Man from Out There had given him a message for Dad!

![]()